However, considering the alternative will help societies to identify and consider the necessary cost of these other ethical values. Of course, there may be good ethical reasons to deviate from a pure utilitarian approach, for example in order to protect rights or promote equality. Typically, some people will be better off.

However, it is important to note that whenever a utilitarian solution to a dilemma is adopted, there will be more well‐being or happiness in the world. Our aim is not to argue that utilitarianism is the only relevant ethical theory, or that a purely utilitarian approach must be adopted. In this paper, we will summarize what utilitarianism is and how it would apply to the COVID‐19 pandemic. As we will discuss, it may be particularly salient and important to consider in the face of global threats to health and well‐being. Yet utilitarianism remains relevant in the 21st century. The theory played a role in antislavery, women’s liberation and animal rights movements. This was a powerful and radical political theory in the 19th century, when large sections of the population were completely disenfranchised and suffered from institutional discrimination. Yet utilitarianism was originally conceived as a progressive liberating theory where everyone’s well‐being counted equally. Utilitarianism is now often used as a pejorative term, meaning something like ‘using a person as a means to an end’, or even worse, akin to some kind of ethical dystopia. ‘severe or profound mental retardation’ as well as ‘moderate to severe dementia’), the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) responded: ‘… persons with disabilities should not be denied medical care on the basis of stereotypes, assessments of quality of life, or judgments about a person’s relative “worth” based on the presence or absence of disabilities or age’. Our civil rights laws protect the equal dignity of every human life from ruthless utilitarianism.Īfter the New York Times reported that some state pandemic plans instructed hospitals not to offer mechanical ventilation to people above a certain age or with particular health conditions (e.g.

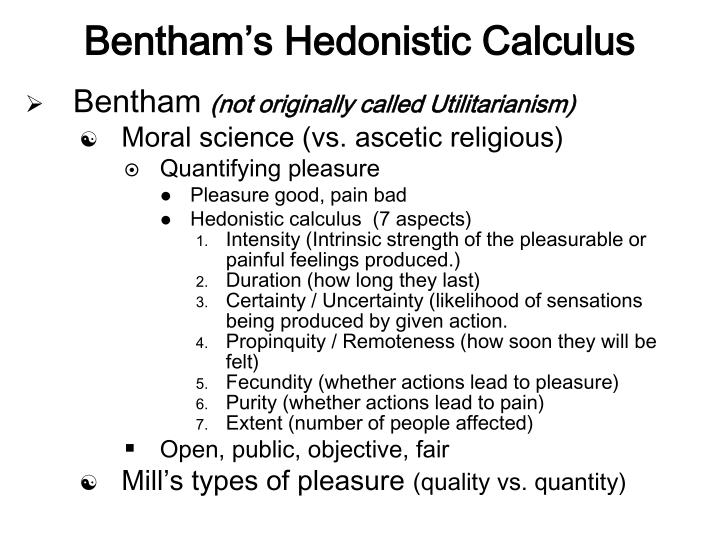

Persons with disabilities, with limited English skills, or needing religious accommodations should not be put at the end of the line for health services during emergencies. The civil rights office of the US Department of Health and Human Services stated that: One ethical theory has been both cited and criticized in public debate about pandemic response. Health systems, facing existing or predicted demand overwhelming capacity, have generated guidelines indicating which patients should receive treatment. The potential threat to large numbers of patients has led to restrictions on movement, employment, and everyday life that have impacted the lives of billions and come at massive economic cost. The COVID‐19 pandemic has posed a formidable and virtually unprecedented challenge to health professionals, health systems and to national governments. Societies may choose either to embrace or not to embrace the utilitarian course, but with a clear understanding of the values involved and the price they are willing to pay. However, clearly considering which options will do the most good overall will help societies identify and consider the necessary cost of other values. In this paper we provide a summary of how utilitarianism could inform two challenging questions that have been important in the early phase of the pandemic: (a) Triage: which patients should receive access to a ventilator if there is overwhelming demand outstripping supply? (b) Lockdown: how should countries decide when to implement stringent social restrictions, balancing preventing deaths from COVID‐19 with causing deaths and reductions in well‐being from other causes? Our aim is not to argue that utilitarianism is the only relevant ethical theory, or in favour of a purely utilitarian approach. It offers clear operationalizable principles. Utilitarianism is an influential moral theory that states that the right action is the action that is expected to produce the greatest good.

HEDONIC CALCULUS EXAMPLE HOW TO

In a pandemic there is a strong ethical need to consider how to do most good overall. It is impossible to treat all citizens equally, and a failure to carefully consider the consequences of actions could lead to massive preventable loss of life. The scale of the challenge for health systems and public policy means that there is an ineluctable need to prioritize the needs of the many.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)